The short answers are no, yes, and it depends.

The short answers are no, yes, and it depends.

How your website terms and conditions are displayed, written, and agreed upon is crucial to their enforceability.

A website’s terms and conditions (T&C) are a contract between a web business and its users and customers. It should be noted that terms and conditions are also called terms of service, terms of use, user agreement, and the like. The T&C must be agreed to in order to be enforceable, just like a paper contract with signatures. However, determining whether the customer or user actually agreed to T&C can be complicated in the world of online transactions and when interacting with websites.

While perceived as onerous to some end users on the Internet, the legal provisions of T&C are necessary to protect website owners from liability. These often excruciatingly detailed clauses provide protection for website owners, but only if the user or consumer has adequate notice of them on the website.

Companies that fail to craft custom designed and legally enforceable T&C for their websites are vulnerable to significant risk. Website owners are open to liability if they are ignorant of the legal guidelines for T&C or, perhaps worse, are too lazy to employ a customized solution for T&C protection. Some of the biggest online retailers in the world have found this out the hard way after being sued by users and losing millions due to their faulty execution of good T&C. If T&C are to have any protective force for a website owner, they must be designed with care and in a manner customized for each website.

An interesting development in Internet and privacy Law concerns the enforceability of T&C in cases where the user does not expressly agree to the terms by means of clicking a box next to ‘I agree’ or similarly obvious call to assent. When a web user indicates their consent to a site’s T&C by clicking on an ‘I agree’ or ‘I accept’ button, this is known as clickthrough or clickwrap.

The click action agreements work as their name implies: the user clicks (takes an action) to give their consent or approval. When properly executed, the clickwrap method of T&C consent is generally considered to be an unambiguous method of agreement to the T&C. However, for various reasons ranging from convenience to deception, some companies have moved away from clickwrap T&C methods to the indirect and arguably more ambiguous mechanism of browsewrap consent.

Under current legal precedent the clickwrap mechanism is not always necessary to obtain legally enforceable T&C. A browsewrap agreement, if posted properly, can be a legally binding alternative for obtaining a user’s consent to T&C. A browsewrap agreement can make website users bound to a website’s T&C simply by using the website in some manner, without any explicit indication of agreeing to the T&C.

Although this practice would appear to be in direct violation of long-standing contract law principles, T&C can be legally binding upon website users through a browsewrap agreement if posted clearly and conspicuously on a website. So the answer to the question ‘are a website’s terms and conditions legally binding if not agreed to’ is: it depends. And by ‘it depends’ we mean “it depends on what you mean by ‘agreed to’.” All agreements must be agreed upon. The difficult question in the online arena arises when the issue of agreement is examined.

Although this practice would appear to be in direct violation of long-standing contract law principles, T&C can be legally binding upon website users through a browsewrap agreement if posted clearly and conspicuously on a website. So the answer to the question ‘are a website’s terms and conditions legally binding if not agreed to’ is: it depends. And by ‘it depends’ we mean “it depends on what you mean by ‘agreed to’.” All agreements must be agreed upon. The difficult question in the online arena arises when the issue of agreement is examined.

The key to an enforceable browsewrap agreement is eliciting some form of action by the user where the T&C are brought to their attention, or making sure your T&C are posted clearly and conspicuously. Unlike clickwrap agreements, browsewrap agreements do not require direct action such as clicking ‘I agree’. Cases have been brought around the country to either enforce browsewrap agreements or defend against them with varying results.

For defendants sued according to the terms and conditions of a plaintiff’s website their defense has been that they did not click on any link that expressly indicated their agreement to the T&C, such as an ‘I agree’ button or ‘I accept’ link, which would demonstrate their approval of the T&C. This seems like a sound argument, especially in light of centuries-old contract law, which has consistently mandated that the terms of any agreement be expressly agreed upon.

Yet some cases have held that this type of approval is not required. Before online contracts came into existence the written signature came to be considered the standard for a customer’s acceptance of terms. Notarization took proof of such acceptance a step further by witnessing the signature on an agreement. The digital age, however, allows for a different form of proof for the acceptance of agreement or contract terms. A more nuanced approach basically requires knowledge of the agreement and some form of action on the part of the user, which indicates acceptance of the agreement.

First, the website must provide some form of notice of the T&C. The form of the notice is crucial to the enforceability of the T&C. Because browsewrap agreements lack the affirmative consent mechanism of the clickwrap agreement, the notice mechanism must comply with certain standards in order to be deemed to have provided adequate notice to the user. Both the language of the notice and its conspicuous positioning on the website are essential in providing actual, or what the law calls ‘constructive’, notice to the user. When these components are properly placed within a notification method, it is assumed that the user has read, understood, and agreed to the T&C.

This is where customization comes into play. Most websites have their own design features. Therefore simply taking the language of one site’s T&C and placing it onto another is likely to fail as an effective means of communicating the T&C to the user. The law deems knowledge by the user of the details of T&C as presumed, so long as the T&C are presented according to certain criteria. Although this may seem like an ideal method to bind users and customers to your T&C, the problem lies in the ambiguity of the legal guidelines in existence to date. While there are a few general guidelines to help web businesses post their T&C effectively, unfortunately there are no absolute rules.

Courts decide the enforceability of browsewrap agreements on a case-by-case basis. There is no one-size-fits-all design for notification on a given website and, as such, it is too easy for website designers to make a big mistake when designing the notification method for their T&C. Therefore borrowing the browsewrap design from one website to use on another is asking for problems. Depending on the business and the terms at issue in a particular dispute, an error in designing enforceable T&C can be financially devastating.

Since several high-profile cases have been decided by the courts on this issue, the facts in these cases are very useful to web-based businesses to use as guidelines for posting their T&C.

Since several high-profile cases have been decided by the courts on this issue, the facts in these cases are very useful to web-based businesses to use as guidelines for posting their T&C.

We’ll start with the case of Zappos.com, the online shoe and clothing retailer that was acquired by Amazon.com in 2009 for over a billion dollars. In 2012 Zappos’ computer system was hacked and its 24 million customers were in danger of having their personal and financial information stolen. A class action lawsuit was brought against Zappos (In re Zappos.com Inc., Customer Data Security Breach Litigation) and the Nevada Federal Court was tasked with deciding whether Zappos adequately protected its customers from the harm they suffered through this massive data breach.

The case initially hinged upon Zappos’ browsewrap T&C provision, which called for arbitration of all disputes. If all of Zappos’ customers agreed to the T&C properly, the class action suit would have to be dismissed and the customers would have to bring their claims through arbitration. The Court stated that “the advent of the Internet has not changed the basic requirements of a contract”, where a “meeting of the minds” and “manifestation of assent” is required to make an agreement enforceable.

The concept of notice was at the heart of the Court’s decision, which held that Zappos’ T&C were unenforceable. Zappos’ T&C (named “Terms of Use”) were “inconspicuous, buried in the middle to bottom of every Zappos.com webpage among many other links, and the website never directs a user to the Terms of Use. No reasonable user would have reason to click on the Terms of Use ….” This decision, which made all of the terms of Zappos’ T&C unenforceable, was a colossal blow to Zappos. Zappos provides Lesson #1 for browsewrap T&C: make sure they’re conspicuous.

Although some critics equate browsewrap agreements to “no contract”, courts have upheld browsewrap agreements with the notion that acceptance of T&C does not always require clicking ‘I agree’. As long as the user was made aware of the T&C, a browsewrap agreement has been upheld as enforceable. In some cases use of a website has also been deemed as acceptance of a site’s T&C.

A Federal Court in New York (Register.com v. Verio) upheld a browsewrap agreement, stating that “the act of using the website to perform a WHOIS search was the same as an acceptance”. The Court took the position that standard contract law of offer and acceptance applies on the Internet. Again, the conspicuousness of the T&C was an essential component of the determination. The consent of the user must be viewed as offering readily available information for “informed consent”.

In Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp. the Court said: “where consumers are urged to download free software at the immediate click of a button, a reference to the existence of license terms on a submerged screen is not sufficient to place consumers on inquiry or constructive notice of those terms”.

It’s clear then that there is a distinct lack of clarity when it comes to the enforceability of browsewrap T&C agreements. Yet there are a few guidelines that should be meticulously followed when offering users a T&C agreement in exchange for website services. The T&C should not in any way be obscured or hidden from the user. A clearly placed notification of the T&C should be obvious to the user.

The T&C should be conspicuous enough that any reasonable person would notice it. A clearly visible statement, which tells the user that by downloading a product or accessing a site or page they are agreeing to the terms of use. As long as your T&C are obvious to the user, and readily available, clicking ‘I agree’ is not always necessary.

Hiding anything from the user (other than the ‘I agree’ button) may be deemed deceptive. “Informed consent” should be the catchphrase to keep in mind when designing an enforceable T&C provision using the browsewrap model.

Will my T&C be enforced as a browsewrap agreement?

Unless there is a court decision relating to your T&C, you can’t be sure. However, there are ways to post your T&C that will greatly increase the likelihood of them being enforced as a browsewrap agreement.

Following the Clear and Conspicuous rule

In the court cases above you see the word ‘conspicuous’ a lot. To follow the clear and conspicuous guidelines you need to understand what might qualify as conspicuous. Although the law does not give an exact definition of what conspicuous is, it does provide you with some excellent guidelines to follow. The term conspicuous is not limited to any one type of document. It is used for terms and conditions, disclaimers, privacy policies, disclosures, contracts, and other documents.

So What Is Considered Conspicuous?

So What Is Considered Conspicuous?

The Federal Trade Commission, state of California, the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), Google, and others define conspicuous in similar ways. Below are a few examples:

Here is a summary of the UCC’s definition of conspicuous:

“Conspicuous”, with reference to a term, means when written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person would notice it. Whether a term is “conspicuous” or not is a decision for the court. Conspicuous terms include the following: (A) a heading in capitals equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, or in a contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or smaller size; and (B) language in the body of a display in larger type than the surrounding text, or in a contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from the surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

California has its own definition of what qualifies as conspicuous when complying with The California Online Privacy Protection Act [CalOPPA] for privacy policies.

The hyperlink (to the privacy policy) uses a color that contrasts with the background color of the web page or is otherwise distinguishable. It is written in capital letters equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text. It is written in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from the surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

Google has requirements for posting disclaimers when using their AdWords program. Here is how they require you to post disclaimers on your website:

“In a prominent location, above the fold of the page, with every claim linked to it by an asterisk (*) the link should be the same text font/color/size as the rest of the content.”

The FTC has a more detailed explanation of clear and conspicuous that you can read by Clicking Here:

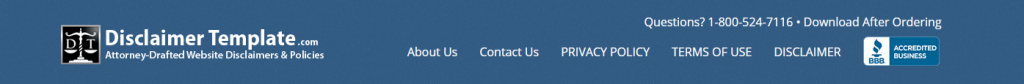

Here is an example of posting your terms of use, privacy policy, and disclaimer conspicuously:

Although the links to the documents are at the top of the website (header), you can also put them on your left or right sidebar as shown below:

What is essential is that the links to your important website documents are above the fold of the page.

Conclusion

If we look at past case law, state laws, FTC regulations, and UCC laws, we will come up with a couple of obvious guidelines to comply with the clear and conspicuous rule:

1. Always place the link to your terms and conditions above the fold of your web page

2. Make the link to your terms and conditions stand out from the text surrounding it by using a larger font, all caps, a contrasting color, or an asterisk.